The unwieldy, internally variegated, and contested traditions that one might nevertheless nominate as black critical theory and black artistic practice, respectively, have had difficult relationships with various traditions of scholarly and aesthetic formalism (though these are, of course, hardly discrete designations). To begin with, the intellectual and artistic forms associated with blackness have typically been regarded by established traditions of formalism with, at best, skepticism.

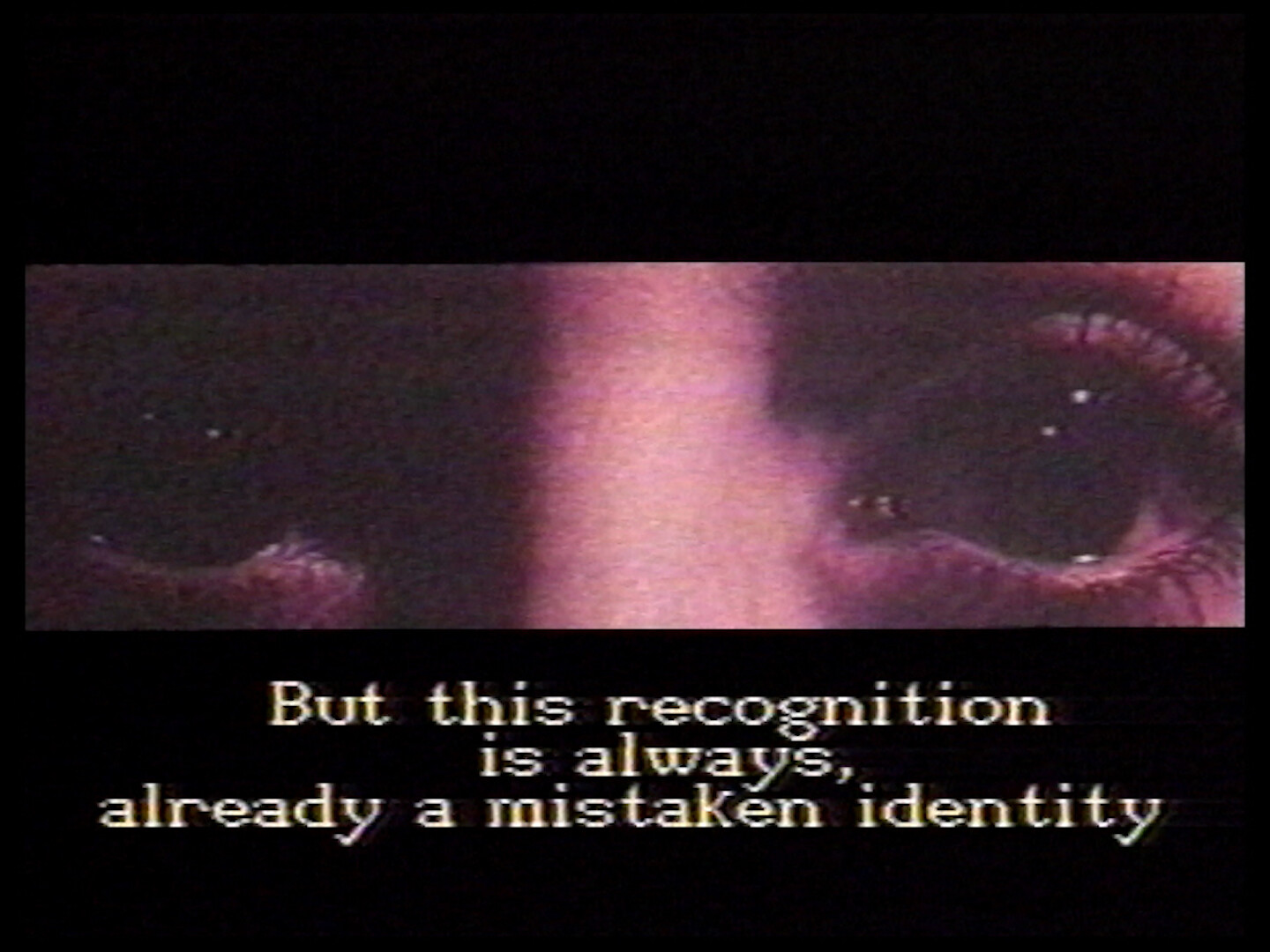

The cumulative process of “mulatto production” constructs various no-man’s-lands within otherwise emancipatory cinema, film, and visual culture, from which certain kinds of Black female subjectivity must remain absent. While Fanon waits for himself in the cinema, at first blush Fanon’s “woman of color” has nowhere to look for her own image. Losing Ground is radical in how it breaks with this model.

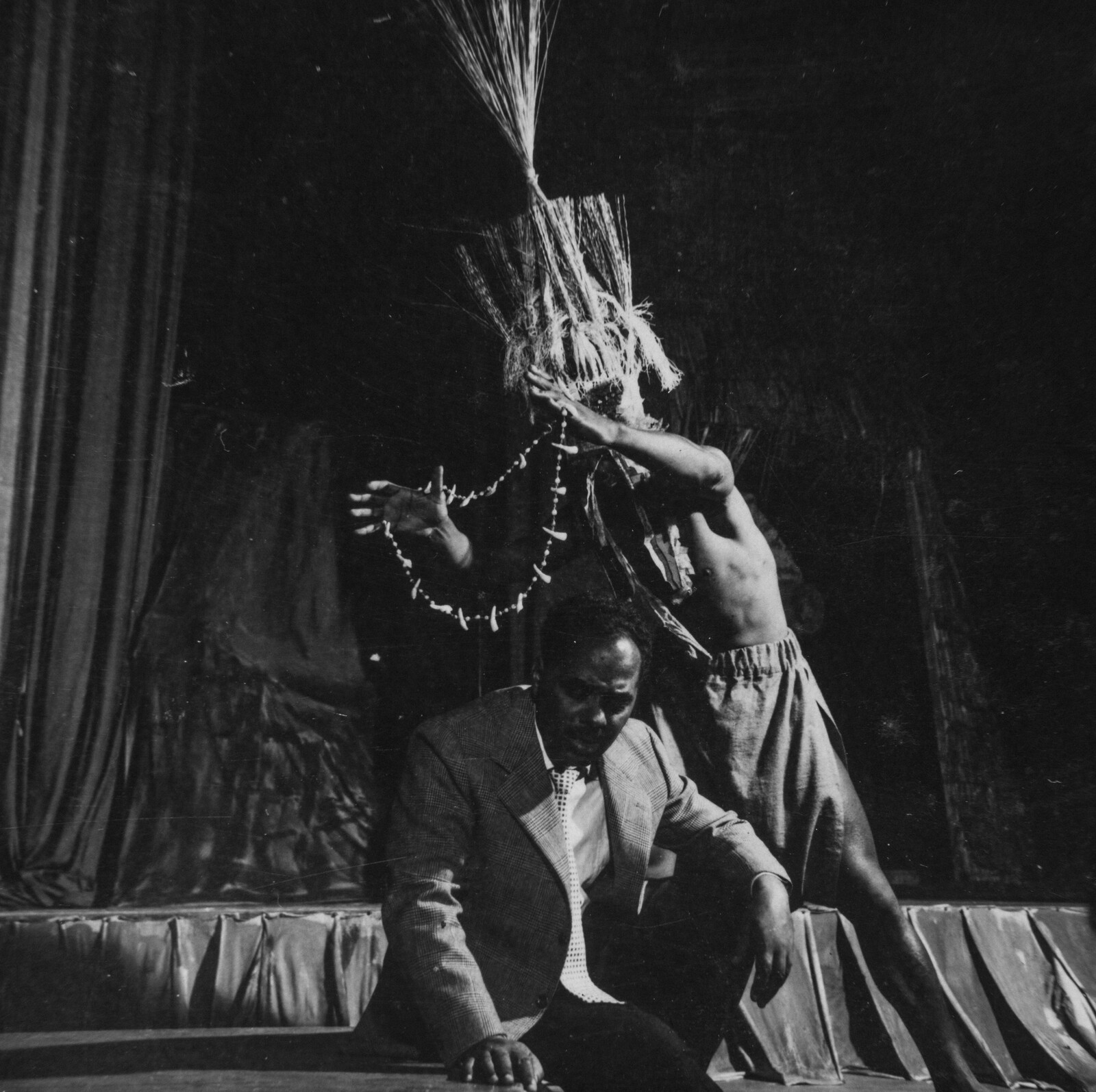

This text might be framed as an offering, an attempt at releasing latent animist lines of possibility for what late twentieth-century works like Bronze Head might do for us in our current climate of rising anti-queer sentiment, on the African continent and elsewhere.

Intensity cannot be destroyed. What exceeds the shape things take cannot properly be located. blackness cannot be captured because blackness is not. It moves. Parastratum, it multiplies all ecologies it comes into contact with.

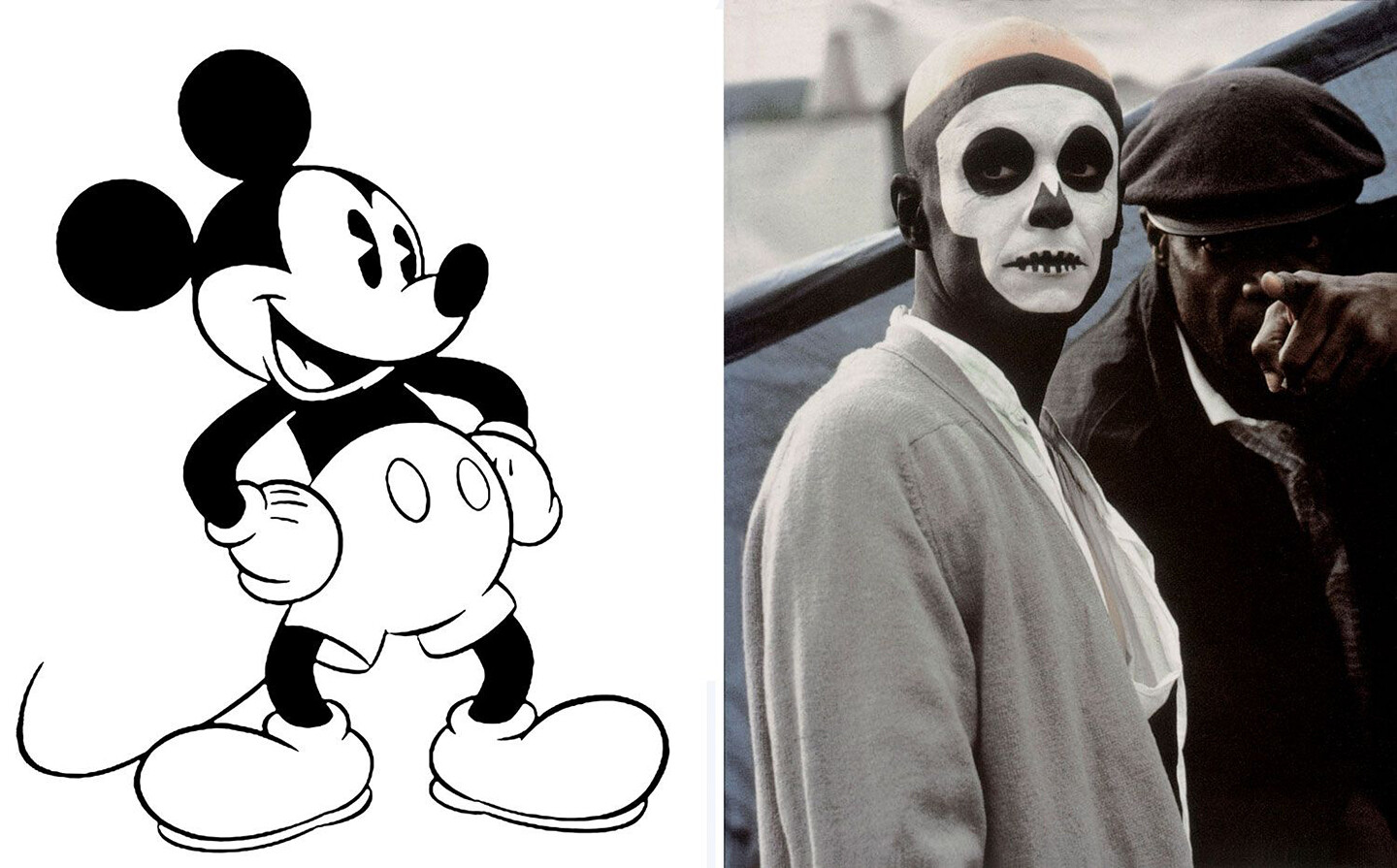

H.D.’s HERmione and Kenneth Macpherson’s Borderline

Elizabeth Povinelli’s anthropology of the otherwise locates itself within forms of life that run counter to dominant modes of being under late settler liberalism.

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, The Inheritance