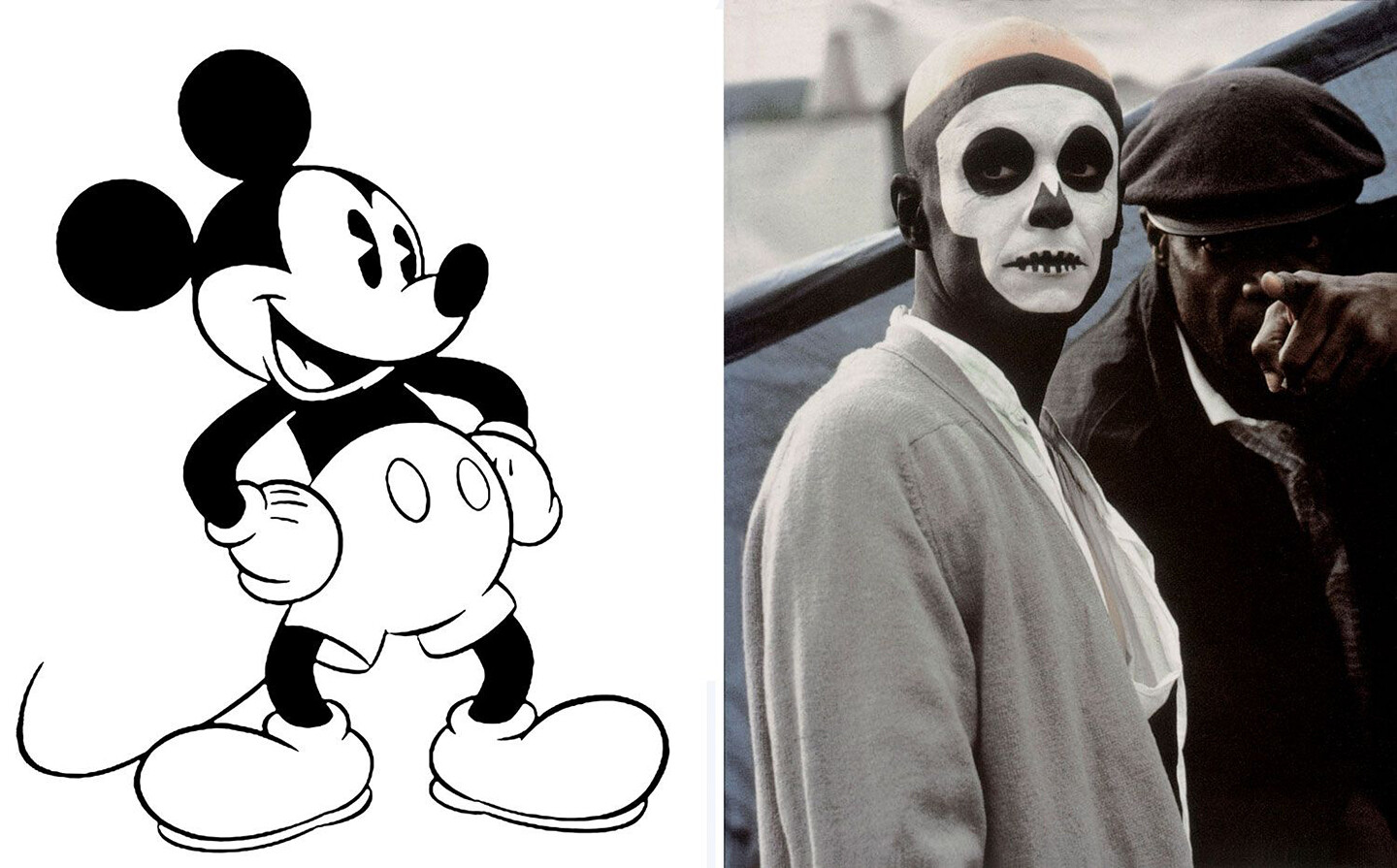

Even if images today are flexible and manipulated, and even if passive spectacle is over and we have all become producers of images, we are always reacting against already established image-myths, and suspicion, revolts, and fragmentations only actualize their exhausted bones. But rather than attempt a media theory, here I still write to merely answer the question: Who pierced the eyes of Assum Preto?

The unwieldy, internally variegated, and contested traditions that one might nevertheless nominate as black critical theory and black artistic practice, respectively, have had difficult relationships with various traditions of scholarly and aesthetic formalism (though these are, of course, hardly discrete designations). To begin with, the intellectual and artistic forms associated with blackness have typically been regarded by established traditions of formalism with, at best, skepticism.

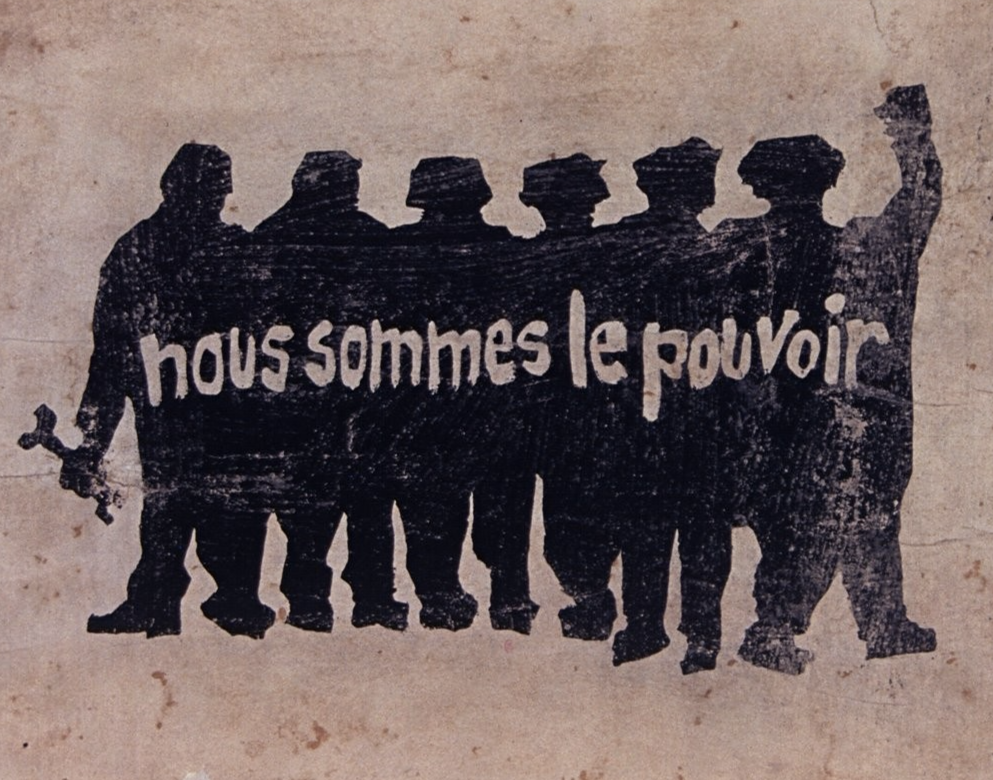

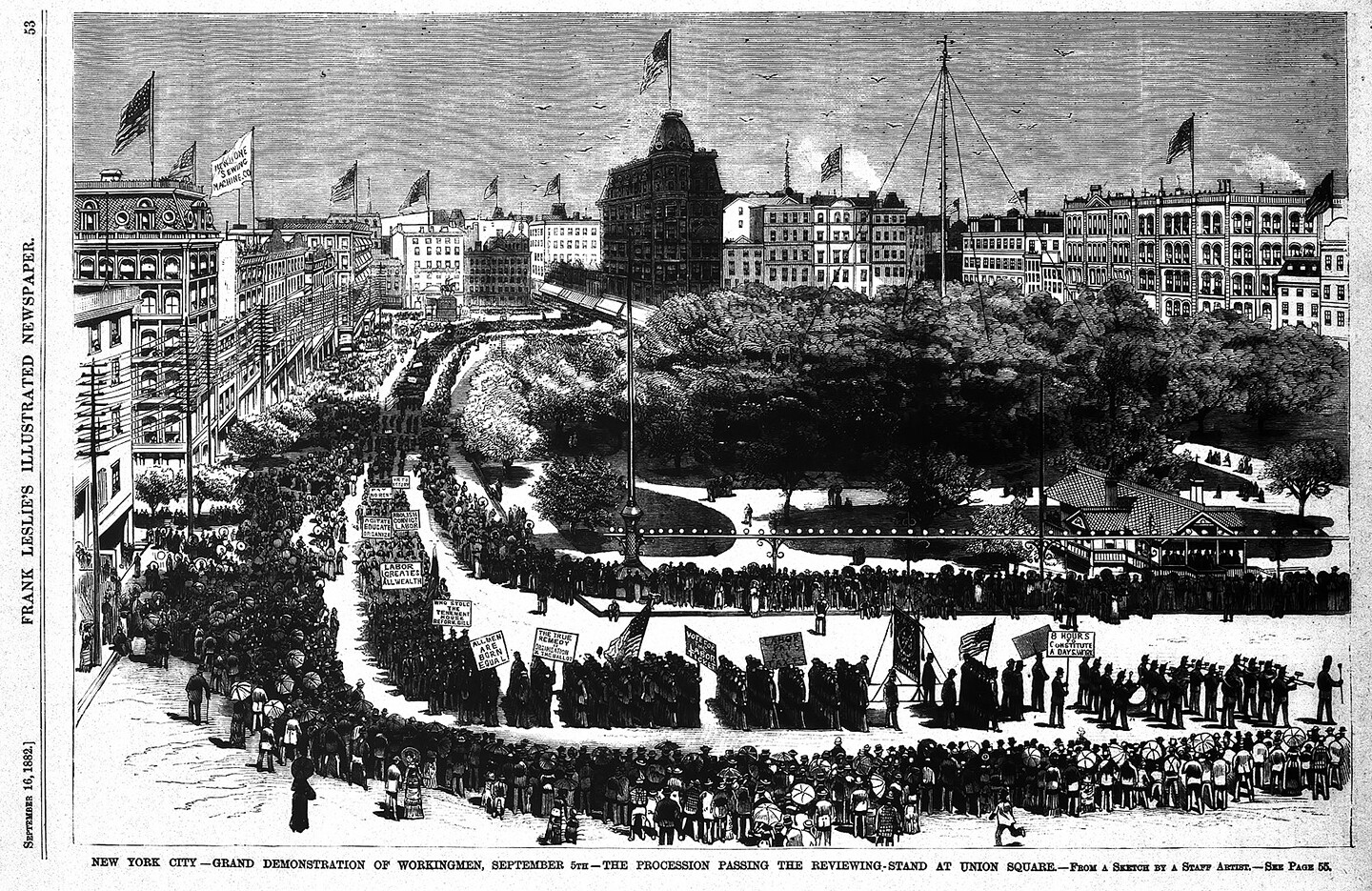

The workers movement wasn’t defeated by capitalism. The workers movement was defeated by democracy. This is the problem which the century puts to us. The matter in front of us, die Sache selbst, that we must now try to think through.

If many in the West today have the sense that the world is coming to an end, it is very much their world that is ending; other worlds were invaded and ripped apart long ago, yet the peoples in question refused to disappear—or, as with the Creole populations of the Caribbean, they became an unprecedented people spanning several aboriginal pasts, the long present of (neo)colonialism, and uncertain futures. Meanwhile the extractivist machine keeps accelerating—even amidst the symptoms of planetary collapse. The million-dollar question—to use an inappropriate metaphor—is to what extent contemporary forms of asymmetrical schismogenesis can maintain or produce forms of life in opposition to financialized and racialized capitalism.

Only the living can visit the dead, not the other way around. We’re there when George Washington buys a slave. We’re there when a tree bears strange fruit. We’re there in the gas chambers, or when Winston Churchill starves to death millions of Indians. And as we in the present are in the past, we are also haunted by those in the future, those not yet born.

As “collective projects” and “collective agency” take on new and complex forms, how can processes of collective self-identification be grasped—not just historically, but also for the social media–driven present? How can such processes be intervened in and shaped? What is the role of disidentification between various “peoples” who cast each other in the role of other, alien, enemy? Are divergences always motivated through negation, by opposition?

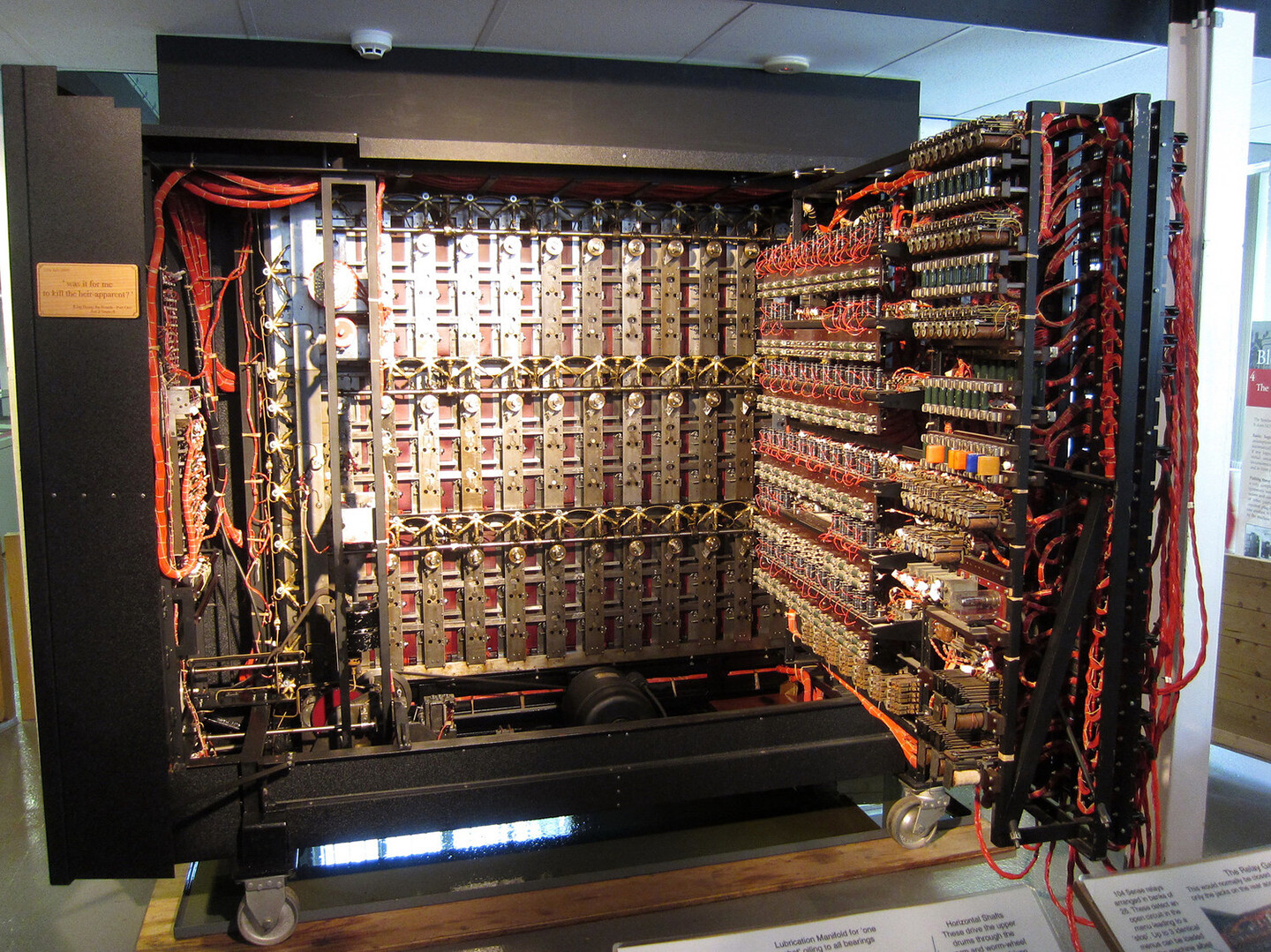

Today’s humans fail to dream. If the dream of flight led to the invention of the airplane, now we have intensifying nightmares of machines. Ultimately, both techno-optimism (in the form of transhumanism) and cultural pessimism meet in their projection of an apocalyptic end.

Cybernetic logic is always about the pursuit of a telos. So if you ask artificial intelligence to write a poem, it is always determined by an end, and this end is calculable. But in what I call tragist logic or shanshui logic we find a similar recursive movement, yet the end is something incalculable. So how can we relate back the question of the incalculable to our discussion of the use of artificial intelligence?

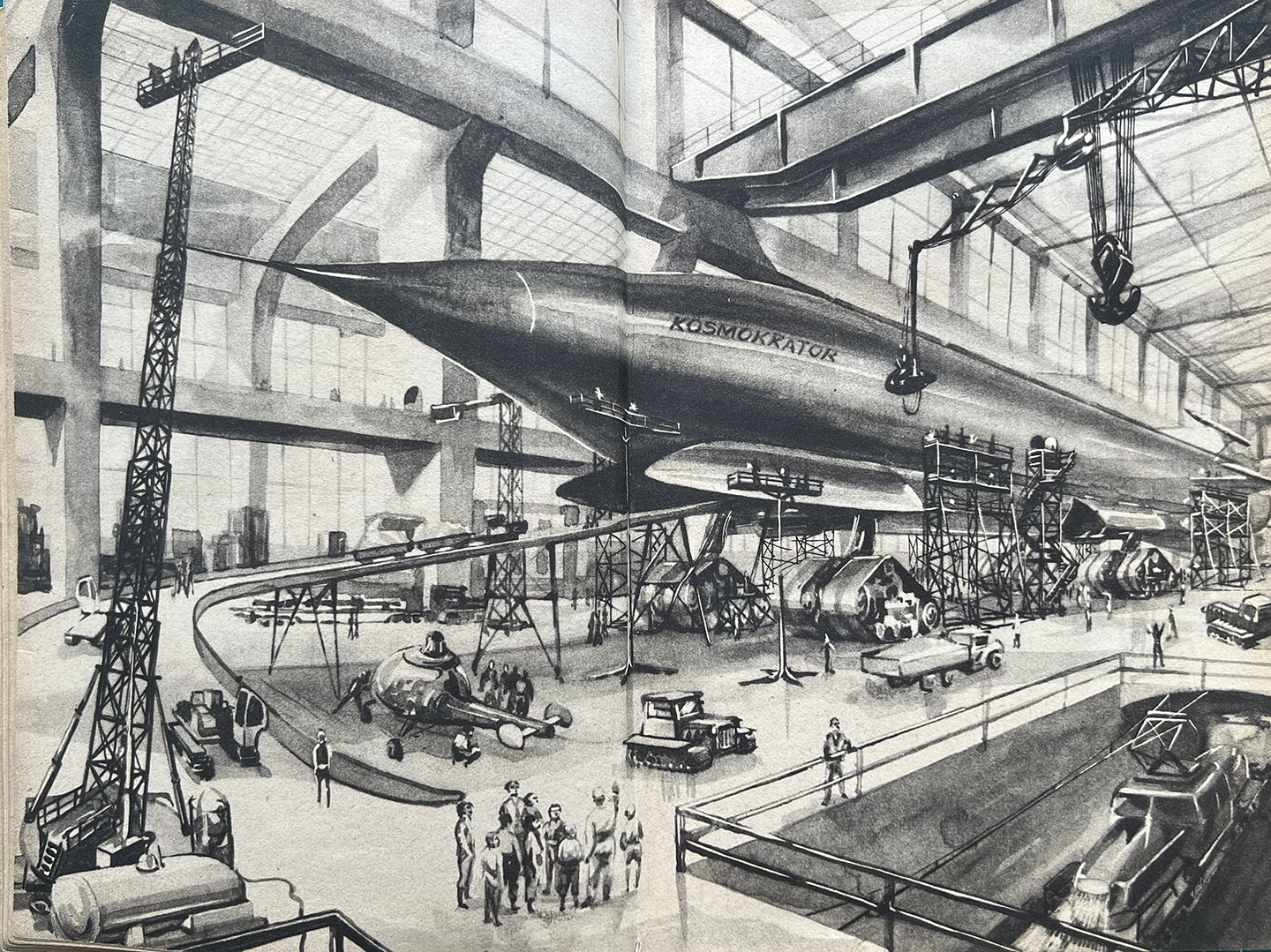

When we speak about cosmic flights and the exploration of space today, we have in mind a dynamic model of technological progress. This dynamic model of progress implies that what we’re doing now in cosmic space will be continued and further improved by the next generation, and so on. The cosmists did not believe in this model. Their questions were along these lines: Why should we be interested in progress if we don’t stand to gain anything from it? If my generation contributes something to cosmic space, how can I benefit from it? I remain mortal, and I remain eternally indentured to progress. I live now—and not in the future. If progress is defined by a dynamic directed towards the future, everyone is yoked to progress, and every generation fast becomes psychologically and physically obsolete.

Intensity cannot be destroyed. What exceeds the shape things take cannot properly be located. blackness cannot be captured because blackness is not. It moves. Parastratum, it multiplies all ecologies it comes into contact with.

It is only possible to speak of independence, beyond a political or economic gesture, when it is revealed that the only common experience is the denial of experience—the end of experience, where one can no longer navigate, where separation and mystery are retained, and a sovereignty of each self is assured even if only as an instant, a space, or a way of life.

Art and Cosmotechnics: Yuk Hui in conversation with Barry Schwabsky

Screening and Discussion: Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri

What do humans do after a successful revolution? The traditional answer is: they become the new masters and begin to impose their will on the losers. Indeed, such is the usual historical dynamic. However, Kojève believed that the working spirit—or rather the spiritualized working body—could be victorious over the animal human body. In other words: he believed that after the proletarian revolution succeeds, proletarians will continue working. But they will not work merely to live or satisfy their desires; they will work to maintain the spiritualized life-form their revolution achieved.

Brazilian authority becomes trapped in producing potlatch after potlatch, transforming its legitimacy into a promise while constantly governing in the name of the exception, in the hope of consumption and expenditure, of enjoying a sacrifice so extraordinary as to erase its spurious and deficient character. It is this debt that allows the colonizer to coexist with the settler insofar as the colonizer can continue to explore, consume, and enjoy through the potlatch, and the settler can see in the colonizer’s enjoyment and expenditure the future birth of law and name. And yet, this birth is always postponed because the authority is burned, inevitably consuming itself in the fire of expenditure, from which the farce of hope and name must be restored with new clothes.