The illogic of exclusion and exception is seductive. Perhaps we will all know ourselves better when we advertise our own place in the world by taking sides with regimes that masquerade as fixed identities and project illusory strength while actually being irreparably fragmented from within, just like we all are. The oppressed, on the other hand, know that a much larger struggle can only be sustained by distinguishing faithful from false witnesses among their own ranks as well as the enemy’s. True identity is forged by how we choose to bear witness, by what endures and grows in meaning as it is transmitted.

If you believe in progress, the old and aged are always to blame for causing the persistent problems of the present, and the young, who supposedly come later, are the solution. This is all very tidy until you wake up one day to find yourself old—and observe that the young who blame you are also the young who are causing the problems of the future, just as you had in your own youth. In this issue, Luis Camnitzer offers advice to the aging—which, to be clear, means all of us—through an anecdotal contribution to the field of intergenerational dialogic studies. He discusses attempts at nonauthoritarian child rearing; his experience, while a student activist, of explaining an art historian’s own obsolescence to his face; and recent moments when he’s realized that his generation has become ineffective at communicating with the young. In other words, Camnitzer fears that his has become the generation suffering from “asshole syndrome”—a diagnosis he and his fellow students used to dole out. Age and power together form a complex configuration, which make empathy and self-assessment all the more important when communicating across generational lines.

In this issue, Charles Mudede proposes that Octavia Butler brought us a viable theory of quantum movement. Who is capable of moving through time to haunt other people in other places and other times, and in which direction? Paradoxically—and there are many paradoxes—just as the hurt have been hurt, the dead can only be dead, and are for that reason no longer able to move forward in time to haunt us. We, however, are alive in our own time, and we feel pain on their behalf. It is we who reach out from the future—our present—to haunt them in the past. We are in fact the zombies of the already dead, mirrors of our own regrets, just as we are presently haunted by messengers from a future time warning us to not repeat what they know will not end well.

Often it seems like we are facing so many endings that we can only be living in the end times—a self-annihilation whose inevitability even appears deliberate. From climate projection to daily news, much of the apocalyptic tone we encounter has an almost celebratory character, as if the end times were more of an ideological construction than a common observation. Certainly a lot of it is macho clickbait or political brinkmanship, and in some cases actual worlds ending. But it also carries a stranger imaginative character in the absence of any significant political imagination by traditional standards. Indeed, taken as a literary tool more than a documentary one, perhaps there is more to the end of the world than we thought.

Part of what makes interviews so engaging to read is that they presume to share ideas on the fly, in a social setting and in the world. In comparison, written essays feel like constructed machines, lean and airtight with beginnings, middles, and ends. No wonder interviews, as a whole, seem a bit decadent in their procrastinatory pleasure. It’s like they catch interlocutors off guard when they should be doing something more serious. Interestingly though, the informality of speech is also a ruse, and a formal challenge for those who prefer to construct words and ideas methodically, because things sometimes spill out that wouldn’t be disciplined into more structured writing and thinking.

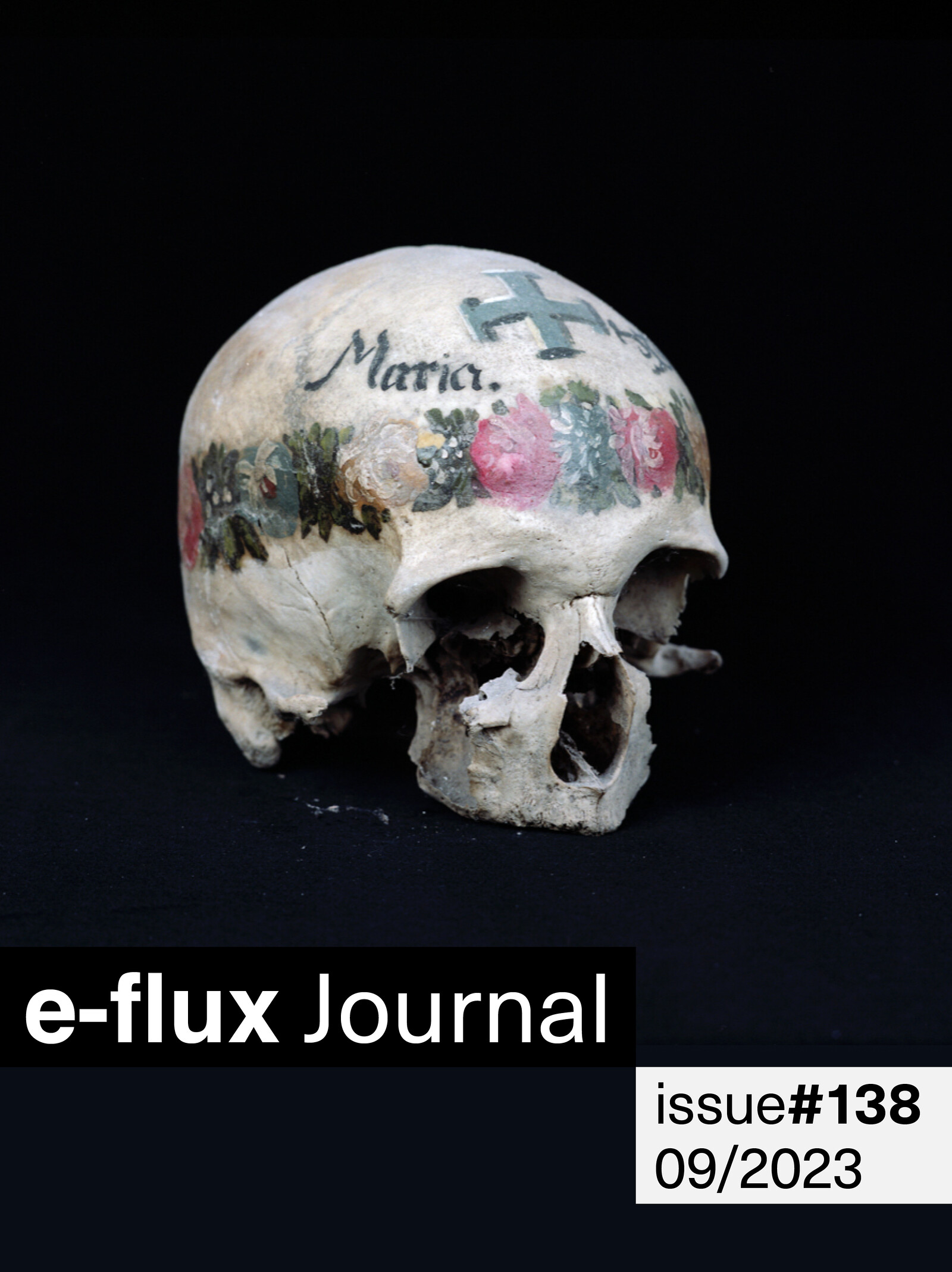

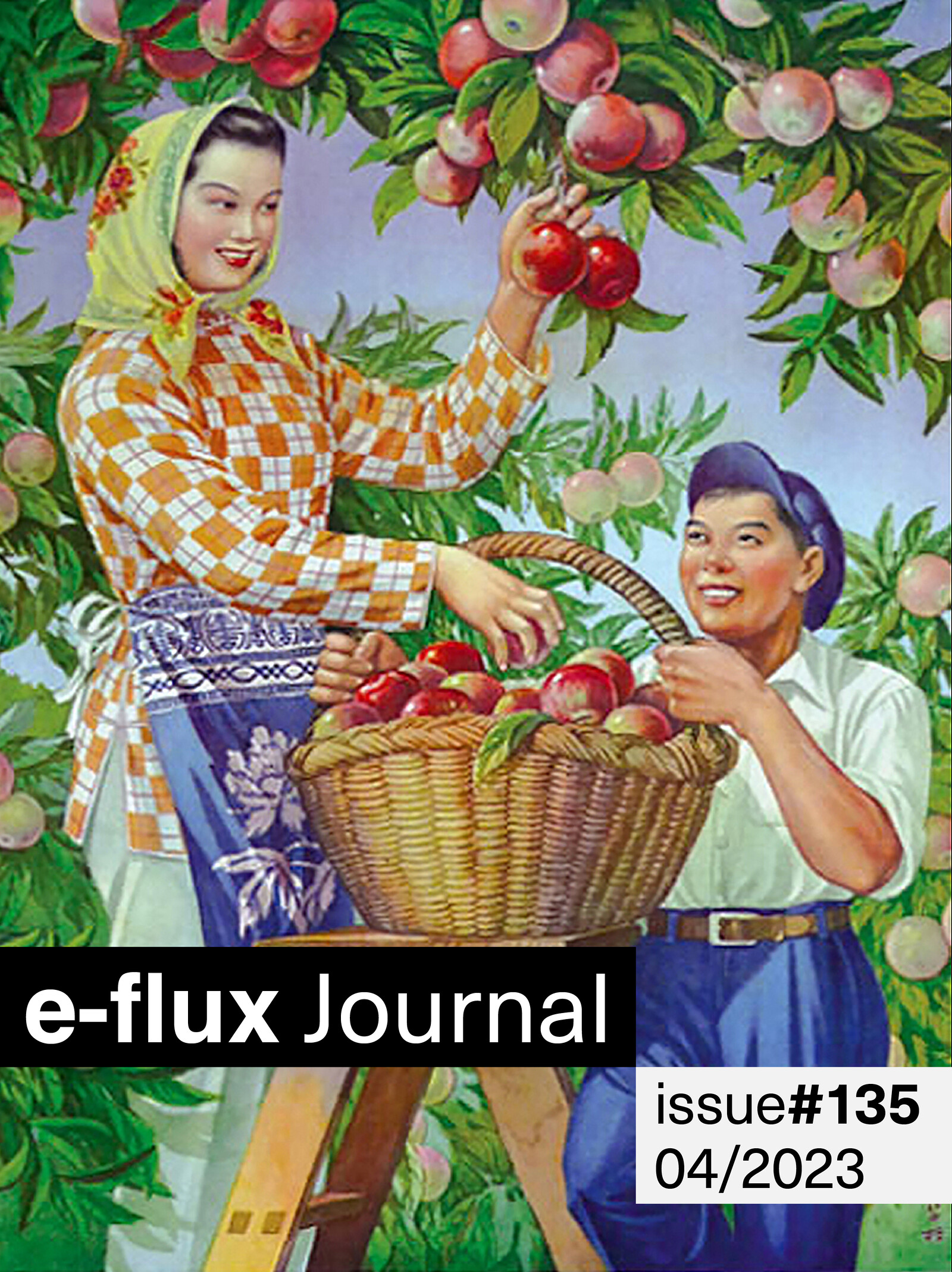

In this issue, Xin Wang details the haunting of China’s contemporary art by socialist-realist pedagogy from the Soviet Union. Perhaps even more significant than this line of influence is its near-total occlusion in Western accounts of China’s avant-garde lineages, no doubt related to Clement Greenberg’s assaults on Soviet socialist realism for epitomizing kitsch. Following Greenberg’s lead, Western scholars may have attempted to be generous by elevating works above lowly pictorial origins, but in doing so, they cleaved them not only from their key influences, but also from a range of formal innovations and attitudes specific to socialist modernity—a version of modernism that continues to persist through its negation, haunting artworks up to today …

In this issue, Boris Groys charts the self-transformation of the working class through labor itself. Workers’ bodies, through their own labor, become spiritualized—artificial forms of their own creation. Since modernity, the working class, held up as a universal whole, has practiced “secular ascesis,” even if by exploitation and oppression. And where does this spiritualized dimension of the working class manifest itself? As art.

In the first e-flux journal issue of 2023, the Ukranian researcher and curator Kateryna Iakovlenko points our eyes at images of forests. The first is from the site of a mass grave outside Izium, a city on the Donets River in eastern Ukraine. The bodies were gone by the time the photo was taken; instead, the photographer shows medics and the surrounding woods. Another is a nineteenth-century photograph of a forest in Tasmania picturing lush trees, which on close examination conceal colonizing British officers. A more recent Instagram photograph shows a feminist Ukrainian Army volunteer living, with others, among the trees they are protecting. A final photo was captured by an occupying Russian Federation soldier’s camera moments before his death outside Izium’s woods. His body remains out of view; his unambiguous vantage point of the exploded forest landscape remains.

“Black Rave”—that’s a great way to think about the sonics of insurgency, a phrase that brings politics back into dance music and culture. Electronic dance music comes from a place of politics, as much as musical purists and Twitter trolls love to insist that “race doesn’t matter” or that “it’s just about the music,” never mind who gets booked to play that music. In the issue, Blair Black and Alexander Weheliye do a wonderful job reminding us of the strategic ways that Blackness and queerness have been removed from electronic music. Which is why the word “rave” is such a racialized one, even as Black people have been raving from the jump.

In this issue of e-flux journal, deep glances at the past hope to make sense of the present by diving into history’s original abysses and early promises. Mi You brings us a refreshingly constructive analysis of this year’s documenta fifteen, its curators, its intended organizational structure, and its audiences. Olga Olina, Hallie Ayres, and Anton Vidokle chart suppressed, banned, and otherwise disappeared languages in a resource that sprawls over geography and time from 1367 to today, showing an ongoing process of erasure and survival that corresponds with the rise of nation-states.

While scientists search the human genome for DNA sequences that set us apart from other species, evidence suggests that we share much of our genetic identity with viruses. Rhizomorphic connections with other creatures, mediated by our viruses, may be happening all the time, along thousands of lines of flight. Infectious agents link humanity with other creatures who live with us in shared multispecies worlds. We are kin with our viral relations.

In this issue of e-flux journal, Carolina Caycedo explains that so many climate activists in South America are murdered by the state that their friends and families have coined a new term for this loss: the dead aren’t killed so much as they are “sown,” like seeds. Their legacies are a source of abundant energy and knowledge to be used in continuing struggles against the collusion of extractive corporations and necropolitical states.

Chances are that in the last couple years, your life has been turned upside down by a pandemic, a war, an economic meltdown, or some combination of these. And you may feel that whatever you were lucky enough to avoid may already be on its way to you. As the coming years are sure to bring more uncertainty, maybe it’s time to prepare. Buy a small armory and move into an underground bunker? Blame foreigners or neighboring countries? Attack each other online? Let’s try instead to consider how our basic needs are met, as the individual and collective bodies that we are.

In this issue, Asia Bazdyrieva offers a broader picture of Ukraine’s significance as a biopolitical resource for Western European appetites. In Ukraine’s operational capacity as Europe’s “breadbasket,” a colonial imaginary unfolds that sees the country’s human, agricultural, and material resources as inert—ripe for extraction by a conqueror who can release their inexhaustible transactional benefits.

It’s unclear how many people still alive today can remember feeling the strange, warm rains that fell over the riverside city of Pripyat on the Ukraine-Belarus border in late April 1986. Pripyat was built in 1970 to serve the nearby Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, dedicated to harnessing the mirnyy atom (“peaceful atom”) for the Soviet Union. For the past thirty-six years, Pripyat and a surrounding exclusion zone of inconsistent bounds bridging swaths of today’s Ukraine, Belarus, and a bit of Russia have been off limits to most human beings.

A couple weeks ago, the world turned upside down again. Dnipro has been bombed again, but not by the Nazis. It’s like a bad dream one can’t wake up from: while thousands of people are being killed in Ukraine and millions are being displaced by the Russian army, nobody really seems to understand the reason or goal of such violence. While Ukraine is being bombed and destroyed, the social fabric of Russia and its economy are disintegrating under sanctions and martial law, and what is rapidly emerging is an isolated, impoverished, fascist state propelled by a death drive.

In the first e-flux journal issue of 2022, Bifo points out a recent social protest movement in China known as tangping (躺平, “lying flat”), in which young people increasingly opt out of the pressure to overwork by taking low-paying jobs or not working at all. In the US, “the Great Resignation” has been the name for four and a half million American workers who left their jobs at the end of 2020. But Bifo reminds us that “resignation” also means re-signification—a new meaning given to pleasure, richness, activity, and cooperation that may unveil a previously hidden egalitarian and frugal sensitivity following the exhaustion of the Western geopolitical order.